A months-long covert experiment has given investigators an unusually intimate look at how North Korea’s remote-work operatives burrow into Western companies. Inside a set of decoy laptops that looked like ordinary developer machines, researchers watched in real time as members of the Lazarus Group’s Famous Chollima unit tested stolen identities, deployed AI-powered job-hunting tools, and attempted to seize control of corporate systems often with the ease of seasoned contractors.

A Surveilled “Workplace” for a Hidden Workforce

The operation unfolded against the backdrop of persistent U.S. pressure on North Korea’s remote-IT worker schemes a cottage industry that had already prompted dozens of enforcement actions by mid-2025. That June, investigators traced more than 100 infiltrated firms, over 80 stolen U.S. identities, and a patchwork of so-called “laptop farms” operating on American soil.

By late 2025, regulators sought more than $15 million in penalties, warning that North Korea’s contractor-style IT roles had quietly enabled the theft of cryptocurrency, proprietary source code, and export-controlled defense data. Into this landscape stepped a research team that decided to flip the model: rather than chase North Korean operators after the fact, they would draw them into an environment built solely to observe them.

The honeypot developed by BCA LTD’s Mauro Eldritch with sandbox provider ANY.RUN consisted of long-running, fully skinned virtual machines designed to resemble overworked American developer laptops. These machines carried realistic browser profiles, IDEs, and usage artifacts, and appeared to sit inside U.S. residential networks, satisfying recruiters who insisted on “American-based talent.”

Capturing a Scheme in Motion

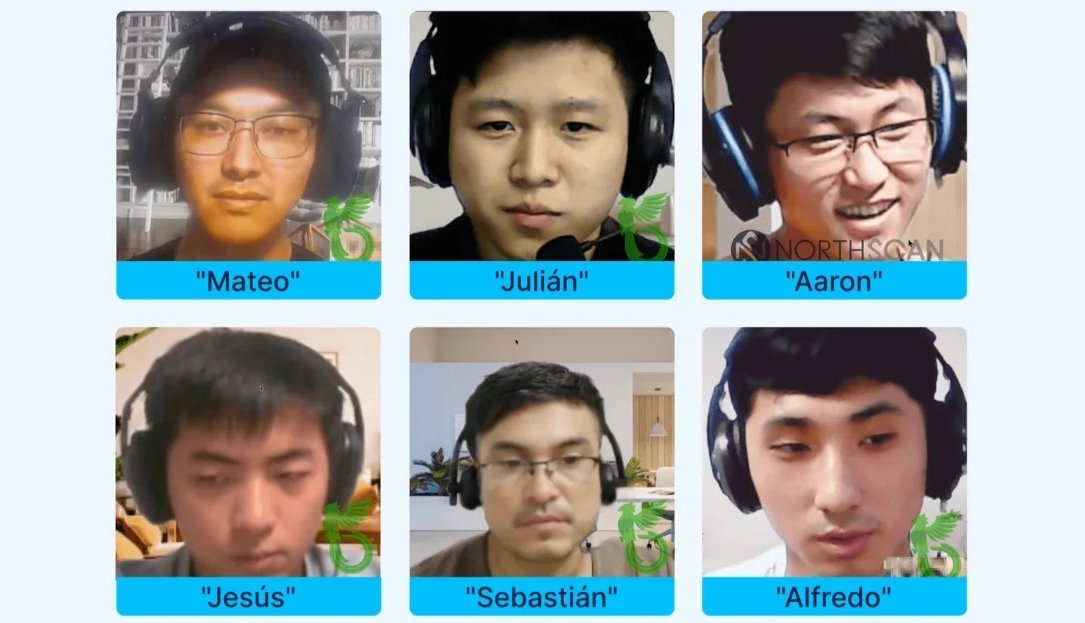

The sting began when an investigator, Heiner García of NorthScan, impersonated a U.S. developer who had been repeatedly spammed on GitHub by a recruiter known as “Aaron” or “Blaze.” Blaze offered a familiar pitch: a cut of a salary in exchange for full access to the victim’s laptop, bank accounts, identity documents and Social Security Number assurances that his “team” would handle the technical work from behind the scenes.

Once Blaze received AnyDesk credentials and a prearranged password, he connected to the decoy machines. He ran a series of hardware verification tools DxDiag, systeminfo and checked browser geolocation results to confirm that the laptop appeared to be inside the United States. Network forensics later showed the connections were funneled through Astrill VPN, a consumer service repeatedly linked to DPRK IT activity.

As he worked, the researchers induced periodic blue-screens, resets, and latency glitches across the system. The disruptions elicited pleading Notepad missives addressed to a persona named “Andy,” along with frantic attempts to troubleshoot while pulling in a colleague using the handle “Assassin.” Hours were spent bypassing CAPTCHAs and reattempting failed logins, every motion captured in detail

Automation, Identity Theft, and Tool-Chain Insight

Once Blaze synced his Chrome profile, the team gained an unprecedented window into Chollima’s toolkit, which leaned less on bespoke malware and more on a constellation of AI-driven job-automation extensions.

Installed tools included Simplify Copilot, AiApply, and Final Round AI services designed to auto-fill applications, rehearse interview answers, and generate responses in real time. Alongside them were OTP-capture utilities like OTP.ee and Authenticator.cc, capable of intercepting one-time passwords once a victim’s identity had been stolen or leased.

The combination suggested a workflow less like traditional espionage and more like an industrialized hiring pipeline: AI to secure the role, rented or stolen credentials to satisfy background checks, and remote-desktop infrastructure to maintain silent control once an employee account was established.

Investigators also watched Blaze deploy Google Remote Desktop via PowerShell with a fixed PIN, layering it over AnyDesk to create redundant access channels. The configuration made the operators’ foothold nearly indistinguishable from legitimate remote-work tooling precisely the ambiguity the scheme relied on.

The Broader Pattern and What It Reveals

What unfolded inside the sandbox echoed a pattern U.S. officials have warned about for years. According to investigators, Famous Chollima often steals CVs outright or persuades junior engineers many abroad to “rent” their identities. The result is a porous hiring ecosystem through which North Korean staff can access U.S. finance, healthcare, Web3, engineering and defense firms while blending into remote-work culture.

The controlled environments allowed researchers not only to observe these intrusions but also to contain them. They monitored file operations and network flows in real time, forced system crashes, and rolled machines back to restore points all without giving operatives an opportunity to pivot to real corporate targets.

For law-enforcement officials, the operation provides unusual clarity: a live demonstration of how human-driven intrusions intersect with AI-powered job automation, KYC evasion, VPN obfuscation, and remote-desktop tooling. Investigators argue the findings highlight the need for tighter identity verification, device-control policies, and greater skepticism toward work arrangements that promise unusually high pay or low effort.