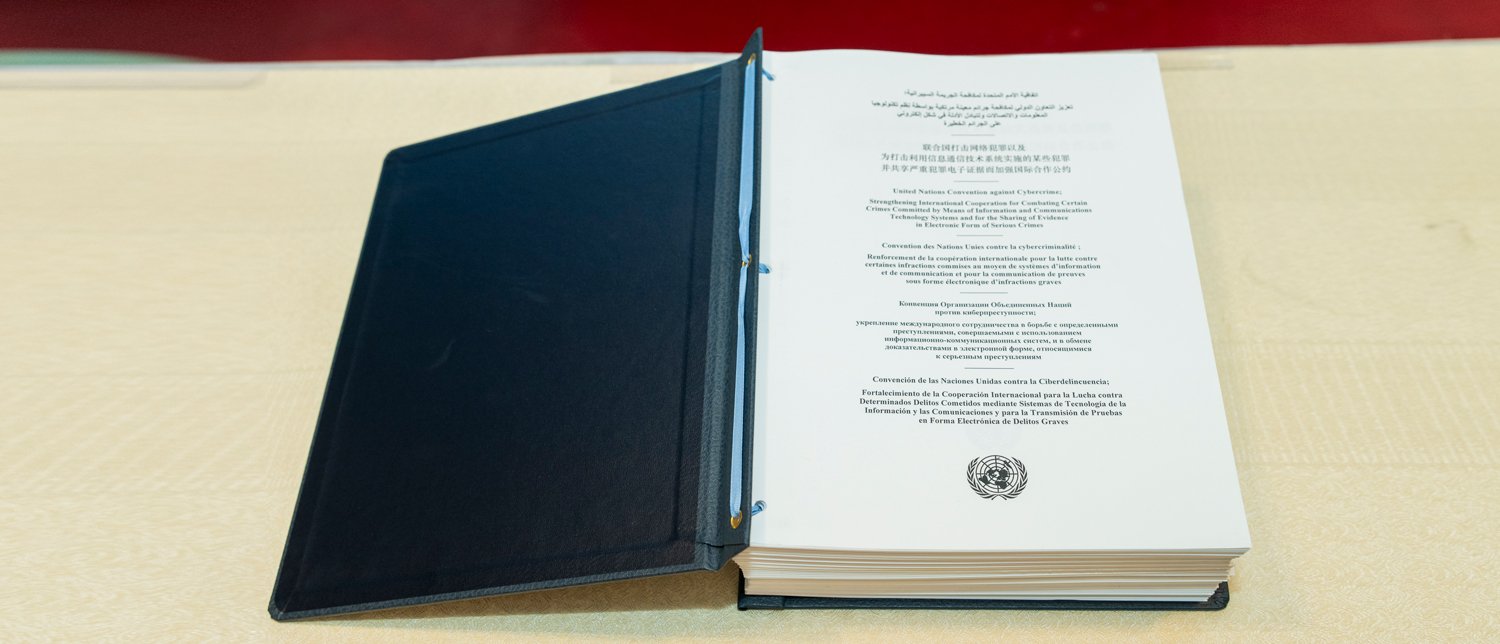

Hanoi, Vietnam | October 27, 2025 — In a landmark step toward building a global framework for digital security, 72 member nations of the United Nations (UN) have signed the Convention on Cybercrime, the world’s first comprehensive treaty designed to strengthen international cooperation against cyber threats.

Adopted after years of negotiation led by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the 41-page treaty establishes a universal legislative structure to help countries investigate, prevent, and prosecute cybercrimes such as hacking, online fraud, identity theft, and child sexual abuse material.

Once 40 countries sign and ratify the agreement, it will become legally binding 90 days after the 40th ratification — potentially setting the stage for the most coordinated global response to cybercrime in history.

“No Country Should Be Left Defenceless”: UN Secretary-General

Speaking at the signing ceremony in Hanoi, UN Secretary-General António Guterres described the treaty as a “powerful, legally binding instrument” that reinforces global solidarity against cybercrime.

“This Convention is a testament to the enduring strength of multilateralism. No country, regardless of its size or stage of development, should be left defenceless against cybercrime,” Guterres said.

The signing comes amid soaring global cybercrime costs, which are projected to reach $10.5 trillion annually by 2025, according to a Cybersecurity Ventures report.

The First Firm to Assess Your DFIR Capability Maturity and Provide DFIR as a Service (DFIRaaS)

Digital Rights Concerns: “A Treaty Without Safeguards”

Despite its ambitious goals, the treaty has faced criticism from several technology policy groups and human rights organizations.

In a joint statement released on October 24, nineteen global digital rights organizations — including Access Now, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), and Human Rights Watch — warned that the treaty “extends far beyond cybercrime,” granting states broad surveillance powers without adequate human rights safeguards.

“The Convention risks legitimizing mass electronic surveillance and could be misused to target activists, journalists, and dissenters under the guise of cybercrime prevention,” the groups said.

Critics argue that while the treaty’s intent is to curb malicious online activities, its vague language could enable intrusive monitoring or criminalize legitimate online expression.

India’s Position: Strategic Opportunity, Legal Ambiguity

It remains unclear whether India was among the 72 nations that signed the treaty in Hanoi. However, experts believe that the country faces a unique set of constitutional and legal hurdles before it can fully align with the UN framework.

According to Raman Jit Singh Chima, Asia-Pacific Policy Director at Access Now, the UN treaty’s provisions on privacy and surveillance are inconsistent with Indian constitutional protections, particularly the Supreme Court’s Puttaswamy judgment (2017) affirming the right to privacy.

“It’s a legally grey area. Unless India makes strong voluntary commitments about how it will implement the treaty, it may not meet the privacy standards laid down by the Supreme Court,” Chima said.

India’s earlier submissions to the UN on the treaty in 2022 included provisions similar to Section 66A of the IT Act, which criminalized “offensive messages” online. The section was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2015 as unconstitutional.

Cybercrime Rising Sharply in India

The urgency of stronger international cooperation is evident from India’s rising cybercrime statistics. According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), 86,420 cybercrime cases were registered in 2023 — up 31.2% from 65,893 cases in 2022. Fraud, extortion, and sexual exploitation accounted for the majority of incidents. Karnataka recorded the highest number of cybercrime cases (21,889), followed by Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra.

Data compiled by the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) under the Ministry of Home Affairs also shows that a significant share of digital scams targeting Indians originated in Southeast Asia, particularly Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos.

Between January and May 2025 alone, Indians reportedly lost ₹4,800 crore to cyber scams traced to these regions, according to the Citizen Financial Cyber Fraud Reporting and Management System (CFCFRMS).

Policy Vacuum: India’s Cybersecurity Strategy Still Pending

Five years after Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a new National Cybersecurity Strategy in his Independence Day speech, the policy remains pending.

As a result, India’s cyber response architecture continues to be fragmented, with overlapping responsibilities across ministries and agencies.

“India has yet to define clear accountability in its cyber governance structure,” Chima said. “Without a consolidated policy framework, India’s ability to contribute meaningfully to global digital cooperation remains limited.”

Global Collaboration Meets Domestic Constraints

For India, signing the UN cybercrime treaty could serve as both a strategic opportunity and a constitutional test.

While the treaty could facilitate greater cross-border investigation and intelligence sharing — essential to tackling international financial fraud and ransomware — it also raises concerns about how such cooperation would align with domestic privacy laws and judicial oversight.

Legal experts point out that India’s current Digital Personal Data Protection Act (2023) focuses on data governance and consent but lacks explicit safeguards against state surveillance.

Aligning with the UN treaty without revisiting these gaps could expose India to constitutional challenges.

Analysis: Between Sovereignty and Cyber Solidarity

The UN Convention on Cybercrime represents a watershed moment in the global governance of cyberspace — but it also underscores the delicate balance between national sovereignty and international cooperation.

For India, the decision to sign will hinge on how it reconciles two competing imperatives:

- The need to protect citizens and businesses from escalating cyber threats, and

- The constitutional duty to uphold individual privacy and freedom of expression.

If implemented with the right safeguards and institutional reforms, the treaty could position India as a leader in global digital diplomacy — reinforcing trust, transparency, and resilience in the interconnected digital economy.

Otherwise, the question will persist:

Can India strengthen cybersecurity without compromising civil liberties?

The UN cybercrime treaty is both an opportunity for global digital cooperation and a test of India’s domestic readiness. Its success will depend on how nations — particularly large digital economies like India — choose to balance control with constitutional caution.