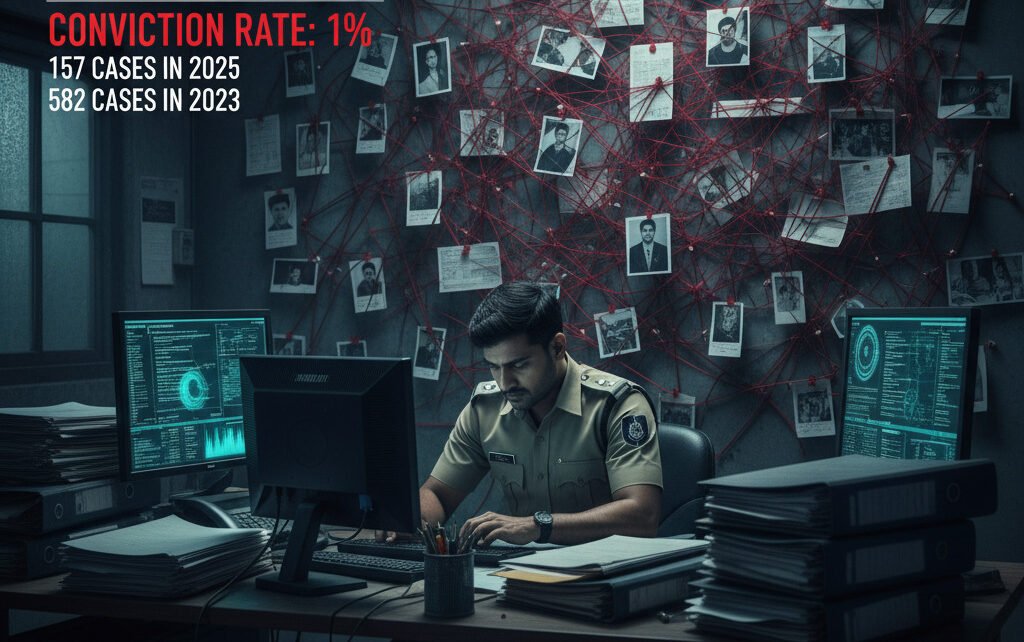

Thiruvananthapuram — Kerala’s capital is facing a cybercrime surge that its police force can barely contain. Data from the City Crime Records Bureau shows that the conviction rate for cybercrime cases remains below 1%, underscoring a crisis in both capacity and coordination.

In 2025, 157 cases were registered in the city, yet investigators managed to arrest key suspects in only two. In five other cases, they caught intermediaries who had lent their bank accounts to fraudsters for small commissions — often claiming ignorance of the crime.

The numbers follow a grim pattern. In 2023, 582 cases were filed, and the main accused were traced in just five. In 2024, out of 307 cases, only four saw the principal perpetrators arrested.

“Cybercrime investigations are unlike traditional cases — the accused are scattered across states and often use fake identities and digital shadows,” said Assistant Commissioner Prakash K. S., who leads the city’s cyber police station.

The Anatomy of a Stalled Investigation

Police officers describe a web of logistical and legal obstacles that slow or halt investigations before they reach the courtroom. Each arrest often requires interstate travel, but under new legal norms, officers must inform the accused’s relatives within 24 hours of detention, forcing them to return immediately after each arrest and delaying follow-up raids.

In most cases, the trail grows cold. Fake SIM cards, dead phone numbers, and deleted call records make tracing suspects nearly impossible. “Call detail records for cases from even a year ago are often unavailable,” Prakash explained. “By the time we locate one suspect, three others have moved on or changed their digital identities.”

The challenges have compounded into a backlog so large that officers estimate 99% of cyber cases go uninvestigated beyond the initial complaint.

A Force Without the Numbers

Behind the statistics lies a deeper structural problem: severe understaffing. The Thiruvananthapuram cyber police station operates with only five officers, including a deputy superintendent and four inspectors. The city’s cyber cell, which handles digital forensics and financial tracking, has just four constables.

The First Firm to Assess Your DFIR Capability Maturity and Provide DFIR as a Service (DFIRaaS)

Together, they are tasked with thousands of active cases involving phishing, investment fraud, and digital extortion. A long-pending proposal seeking 50 additional constables for the station and 15 for the cyber cell remains buried in bureaucratic review.

Without manpower, even the most basic casework — verifying IP logs, filing preservation requests, coordinating with telecoms — becomes a months-long effort. “We are fighting 21st-century crimes with 20th-century resources,” said a senior officer who requested anonymity.

The Broader Struggle Against Invisible Crimes

Kerala, one of India’s most digitally literate states, now faces the paradox of being a hotspot for cybercrime while lagging in cyber enforcement. Experts say the problem isn’t just manpower — it’s mindset.

“Cybercrime units are still treated as auxiliary wings rather than core policing functions,” said a retired DGP who helped set up the state’s first cyber lab. “Until digital policing is integrated into mainstream law enforcement, conviction rates will remain symbolic.”

For victims — often middle-class citizens duped by investment or impersonation scams — the odds of justice are slim. Their complaints, routed through national portals, usually end in temporary freezes or refund attempts rather than criminal prosecution.

As one officer summed up: “Cybercrime is now India’s fastest-growing crime category. But our conviction rate shows — we’re still learning to fight ghosts in the machine.”