Across South-East Asia, a sprawling constellation of industrial-scale scam centers has grown into a lucrative political economy one so entrenched that crackdowns often appear more theatrical than transformative. As governments publicly deny complicity, criminal networks have embedded themselves in state structures, reshaping both regional power dynamics and the global cybercrime landscape.

A Criminal Industry Steps Into the Light

What was once a shadowy network of online fraud rings has evolved into a multibillion-dollar regional industry operating in plain sight. According to regional analysts, scam masterminds across South-East Asia now “operate at a very high level,” obtaining diplomatic credentials, advising political figures and embedding themselves within state institutions.

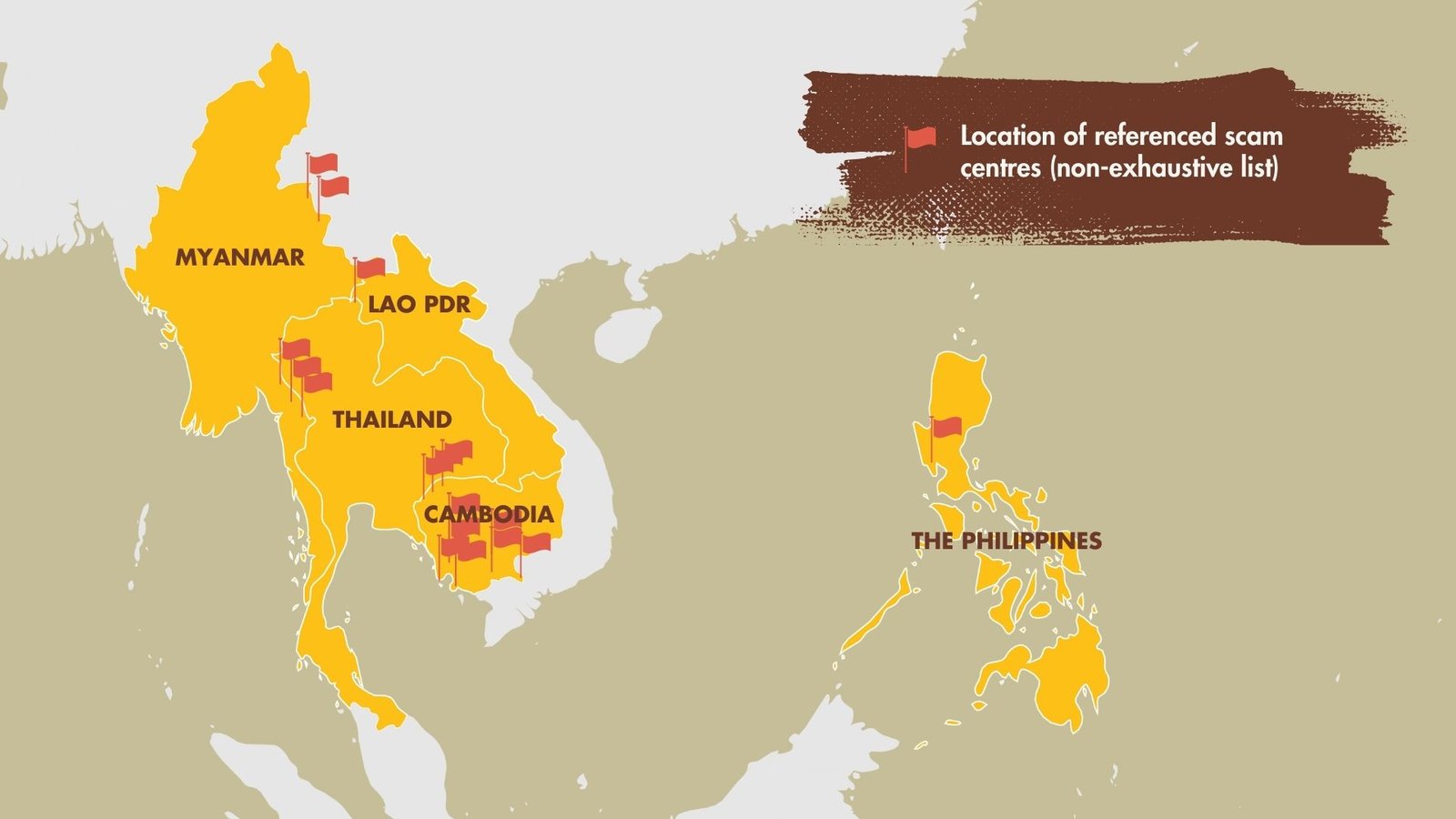

The scale of their operations is striking. In Laos, officials have acknowledged the presence of roughly 400 scam hubs, many clustered around the Golden Triangle special economic zone, a region already long associated with illicit cross-border trade. In Cambodia, investigators from Cyber Scam Monitor an independent collective tracking scam compounds have identified more than 250 sites, many vast enough to rival small industrial parks.

Experts say the openness of these facilities underscores not only local authorities’ tolerance, but also the extent to which criminal actors have become intertwined with political systems.

“This is happening in a very public way,” said Jason Tower of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “The level of impunity is extreme—and in some cases, these actors are becoming state-embedded.”

Economies Rewired by Illicit Profit

The financial incentives are difficult to overstate. Analysts now estimate the global scam economy has ballooned from under $70 billion in 2021 to well into the hundreds of billions by 2024 approaching the scale of the global illicit drug trade.

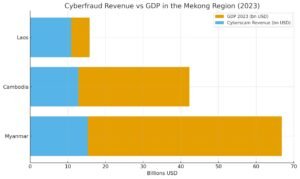

In the Mekong region, cyber-fraud operations alone generated roughly $44 billion in 2024, equivalent to nearly 40 percent of the area’s formal economic output. One U.S. Department of Justice seizure in Cambodia last year $15 billion in cryptocurrency amounted to almost half the country’s annual GDP.

This explosive growth has reconfigured the economic landscape of multiple countries, transforming scam centers into among the dominant engines of regional GDP.

“In terms of gross GDP, it’s the dominant economic engine for the Mekong sub-region,” said Jacob Sims, a cybercrime expert at Harvard University’s Asia Center. “And that means it’s one of the dominant if not the dominant political engines.”

Across Myanmar, revenues from scam hubs have reportedly become a key financial lifeline for armed groups struggling to finance territory and operations in the wake of civil conflict. In the Philippines, the arrest and life-sentencing of a former mayor connected to a major scam center illustrated how deeply the industry has penetrated local politics.

A High-Tech Machinery of Exploitation

At the center of these operations lie “pig-butchering” schemes long-cons that cultivate online relationships before coaxing victims into fraudulent crypto investments. Scammers increasingly deploy advanced technologies to bolster credibility: generative-AI-written messages, deepfake video calls, and cloned websites that mimic regulated financial platforms.

One survey cited by investigators found victims lost an average of $155,000 each, with many reporting the collapse of life savings. Meanwhile, inside the compounds, laborers many trafficked are forced to work under threat of violence, generating relentless streams of messages designed to ensnare targets across the globe.

The industrialization of fraud has prompted comparisons to narco-states, where illicit industries become so embedded that they reshape governance itself.

“Experts say we are entering the era of the scam state,” Tower noted. “This refers to countries where an illicit industry has dug its tentacles deep into legitimate institutions.”

Crackdowns—Or Political Theater?

In late 2024, Myanmar’s junta announced the destruction of KK Park, one of the region’s most notorious scam complexes. Press releases celebrated the leveling of empty buildings food halls, dormitories and even a four-story hospital after bombing operations that lit up the skyline.

Yet the operators were already gone. Thousands had fled across borders; thousands more had simply vanished. Within days, new scam centers began appearing elsewhere, underscoring what analysts describe as a cynical game of “Whack-a-Mole,” where enforcement efforts target convenient mid-level actors while leaving the system intact.

Governments in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos have denied allegations of high-level complicity. Myanmar’s military insists it aims to “eradicate scam activities from their roots,” while Cambodia’s government has called reports it hosts one of the world’s largest cybercrime networks “baseless” and “irresponsible.”