NEW DELHI — On October 16, a seemingly routine procurement notice appeared on an Indian government website. The Lokpal of India, the nation’s highest anti-corruption authority, was inviting bids for “seven white BMW 330Li M Sport (Long Wheel Base) cars”. The estimated cost for the fleet of luxury sedans: over ₹5 crore, or approximately $600,000.

For an institution conceived in the crucible of a massive, Gandhian-style street protest against the very culture of political extravagance and graft, the tender was more than just a procurement decision. It was a profound and jarring symbol of a promise broken. The Lokpal, a term that translates to “Caretaker of People,” was born from the fervent hope that it would be a powerful, independent watchdog, a sentinel for the common citizen against the excesses of the powerful. Instead, it now stood accused of indulging in those same excesses.

The backlash was immediate and ferocious. The purchase ignited a firestorm of criticism, uniting opposition politicians, the activists who had once championed the institution’s creation, and a deeply disillusioned public. The controversy, however, is not an isolated misstep. It is the catalyst that has brought years of simmering discontent about the Lokpal’s dismal performance to a boil, forcing a national conversation on a once-unthinkable question: After a decade of legislative existence and five years of near-total inertia, should India’s top anti-corruption ombudsman be abolished?.

The Weight of a Nation’s Hope: The Promise of the Lokpal

The story of the Lokpal is the story of a dream deferred for nearly half a century. The idea of an independent ombudsman was first articulated in the Indian Parliament in 1963 by the jurist L.M. Singhvi, who coined the Sanskrit term, and was formally recommended by the first Administrative Reforms Commission in 1966. Over the next 45 years, bills to create the institution were introduced in Parliament nine times, only to languish and lapse with each successive government, a testament to a deep-seated political reluctance to create a body with the power to investigate its own.

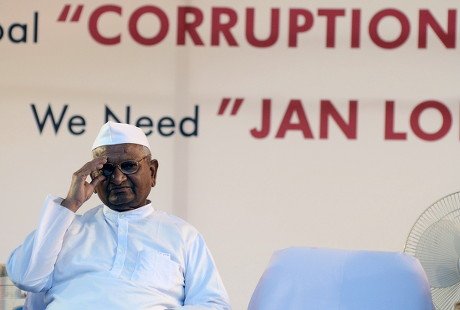

That political inertia was shattered in 2011. In the sweltering April heat of New Delhi, a 72-year-old social activist named Anna Hazare began an indefinite hunger strike at Jantar Mantar, a public square designated for protests. His demand was simple: the government must enact a strong anti-corruption law and create an independent Lokpal. The protest electrified the nation. Fueled by a series of high-profile corruption scandals and a growing sense of frustration with a system perceived as endemically corrupt, the “India Against Corruption” (IAC) movement exploded into a nationwide phenomenon. Millions of middle-class Indians, students, and professionals, many of whom had never protested before, poured into the streets in cities across the country and the diaspora, waving the Indian tricolor and chanting slogans against graft. It was a national outpouring of anger against the “License Raj” culture of bureaucratic control and the kleptocracy it enabled.11

At the heart of the movement was a citizen-drafted bill, the “Jan Lokpal Bill” (People’s Ombudsman Bill), prepared by a team of activists including Arvind Kejriwal, who would later become the Chief Minister of Delhi, and the lawyer Prashant Bhushan. Their version envisioned a far more powerful and independent body than the one proposed by the government. It called for a transparent, civil society-involved selection process and a broad jurisdiction that included the Prime Minister and the judiciary. Tense negotiations between the government and the activists in a Joint Drafting Committee ultimately collapsed, with the two sides unable to agree on the fundamental scope of the ombudsman’s powers.5

Under immense and unrelenting public pressure, the government finally relented. In December 2013, after a tortuous journey through both houses of Parliament, The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act was passed. The final law was a landmark achievement. It established the Lokpal at the national level and mandated the creation of similar bodies, called Lokayuktas, in every state. Its mandate was sweeping: it had jurisdiction to investigate allegations of corruption against the Prime Minister (with certain safeguards), all Union ministers, Members of Parliament, and every level of central government official, from the highest echelons (Group A) down to the lowest (Group D). Crucially, it was given the power of superintendence and direction over any investigative agency, including the powerful Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), for cases referred to it. For the millions who had marched, fasted, and hoped, the Lokpal was not merely a new government body; it was the fulfillment of a social contract, a hard-won promise that the citizen’s voice could, in fact, reform the state. The subsequent failure of the institution, therefore, represents not just an administrative lapse but a profound betrayal of that contract, contributing to a deep and lasting erosion of public trust in the efficacy of democratic action.

A Record of Inertia: An Autopsy by Numbers

The Lokpal became operational with the appointment of its first chairperson and members in March 2019, more than five years after the law was enacted. In the years since, its performance has been a study in institutional paralysis. An examination of the Lokpal’s own data reveals an institution that has failed to meet even the most basic metrics of success, becoming a bureaucratic black hole rather than a beacon of accountability.

The most telling statistic is the precipitous decline in public engagement, a clear indicator of collapsing public faith. After an initial period of interest, the number of complaints filed with the ombudsman has fallen off a cliff. From a peak of 2,469 complaints in the 2022-23 fiscal year, the number plummeted to just 233 in the first six months of the current year (up to September). Out of a total of approximately 6,955 complaints received since its inception, a staggering 90% were filed in its first four years. The sharp drop-off suggests that citizens have effectively given up on the institution as a viable avenue for justice.

For the few who do file complaints, the chances of their case being heard, let alone investigated, are vanishingly small. The Lokpal has erected a formidable procedural wall, dismissing an astonishing “nearly 90%” of all complaints received, primarily on the technical grounds that they were not filed in the “correct format”. This has led to accusations that the institution is more focused on bureaucratic compliance than on addressing the substance of corruption allegations. As RTI activist Anjali Bhardwaj noted, “Most complaints are being dismissed on technicalities such as format errors, while serious corruption allegations go unaddressed”.

The numbers that truly define the Lokpal’s record are those that measure its core function: investigating and prosecuting corruption. Here, the record is abysmal. In over five years of functioning, out of nearly 7,000 complaints, only 289 have led to a preliminary inquiry. A mere 24 have resulted in a full investigation being ordered, and just six or seven cases have seen the Lokpal grant a sanction for prosecution. The institution created to hunt the biggest predators in the ecosystem of corruption has, in practice, become what one media report dubbed the “god of small things”. An analysis of the few cases where prosecution has been sanctioned reveals a focus on relatively low-level officials. These include a State Bank of India branch manager who allegedly took a bribe of ₹4 lakh ($4,800) for a loan, and a mint employee accused of embezzling about ₹53,000 ($635). While these are instances of corruption, they are a far cry from the “big-ticket” scandals involving high-ranking public functionaries that the Lokpal was specifically created to tackle.

Compounding this record of inaction is a glaring lack of transparency. The Lokpal is mandated by law to prepare an annual report on its activities to be laid before Parliament, a key mechanism for public accountability. Yet, it has failed to upload any such report to its website since the 2021-22 fiscal year, keeping the public and Parliament in the dark about its internal functioning and the disposition of thousands of complaints.

The Anatomy of a Failure: Political Sabotage and Structural Flaws

The Lokpal’s dismal performance is not an accident of bureaucratic incompetence. It is the predictable outcome of what critics describe as a systematic and deliberate process of institutional starvation, beginning even before its first member was appointed. The political establishment, which had the institution forced upon it by public pressure, appears to have ensured from the outset that the watchdog would be born without teeth.

The first and most significant act of sabotage was delay. The Lokpal Act was passed in 2013, but the government took more than five years to appoint the first chairperson and members in March 2019. For half a decade, the law existed only on paper, a hollow victory for the activists who had fought for it. This delay was a clear signal of the government’s lack of political will to operationalize a body that could potentially investigate its own officials.

When the appointments were finally made, the selection process itself was mired in controversy, raising immediate questions about the Lokpal’s independence. The high-powered selection committee is supposed to include the Leader of the Opposition (LoP) in the Lok Sabha to ensure a non-partisan choice. However, the government argued that since no party had met the 10% seat threshold to be formally recognized as the opposition, there was no LoP. The leader of the largest opposition party was invited to the selection meetings only as a “special invitee,” an offer that was rejected as “mere tokenism”. This resulted in a “truncated” selection committee dominated by the government and its appointees, which critics argued was inherently biased towards selecting candidates favored by the ruling party.

Even after its belated constitution, the Lokpal was left as a body without organs. The Act explicitly empowered the ombudsman to establish its own independent Inquiry Wing and Prosecution Wing to ensure that it would not have to rely on the very government agencies it was meant to oversee. Yet, for years, these crucial wings were never set up. In a shocking display of institutional apathy, the Prosecution Wing was formally notified only in June 2025—a full twelve years after the law was passed. This failure forced the Lokpal to refer cases for preliminary inquiry to the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) or for investigation to the CBI, effectively undermining its own independence and perpetuating the problem of the “caged parrot” it was designed to solve.

The Act itself contains structural weaknesses that have proven fatal in practice. Legal analysts point to several design flaws, including a strict seven-year limitation period, which prevents the Lokpal from taking up older cases of corruption, and overly rigid procedural requirements for filing complaints. The fact that nearly 90% of complaints are dismissed on technical grounds is a direct consequence of these legislative hurdles, which make the institution inaccessible and ineffective by design. The cumulative effect of these delays, compromises, and design flaws was to ensure the watchdog was neutered before it could even begin its work, pointing to a deliberate strategy of political containment rather than mere bureaucratic lethargy. The crisis of credibility became so acute that in 2020, a judicial member of the Lokpal, former Chief Justice Dilip B. Bhosale, resigned from his post, citing the institution’s deep-seated “dysfunctionality” in a powerful indictment from within.

A Costly Symbol: The Case For and Against Abolition

It is in this context of profound failure that the tender for seven BMWs landed like a match on dry tinder. The purchase crystallized the image of the Lokpal as an institution utterly disconnected from its public service mission, a sinecure for retired officials that had become a symbol of the very problem it was meant to solve.

The outrage was swift and bipartisan. Senior Congress leader P. Chidambaram asked pointedly, “When Honourable judges of the Supreme Court are provided modest sedans, why do the Chairman and six members of the Lokpal require BMW cars?”. Abhishek Manu Singhvi, who once chaired the Parliamentary Committee on the Lokpal, called it a “tragic irony, the guardians of integrity chasing luxury over legitimacy”. The public mockery was relentless, with commentators coining derisive nicknames like “Jokepal” and “Shauq Pal” (indulgence-pal) to capture the sense of betrayal.

The Lokpal’s official justification was, in itself, revealing. Unnamed sources within the organization defended the purchase by pointing to Section 7 of the Lokpal Act, which stipulates that the chairperson and members are entitled to the same salaries, allowances, and service conditions as the Chief Justice of India and Supreme Court judges, respectively. Since Supreme Court judges had recently been allotted BMW 3 Series cars, the Lokpal was simply claiming its statutory entitlement. This defense exposed a fundamental institutional identity crisis. The Lokpal, born from a populist street movement, had abandoned the ethos of a people’s ombudsman and instead adopted the entitlements of a high judicial office, prioritizing status and perks over its public service mission. This profound disconnect between its origin and its self-perception is the deepest indicator of its dysfunction.

This episode has galvanized the argument for abolishing the institution altogether. Proponents of this view argue that the Lokpal has demonstrably failed its primary mandate, has not prosecuted a single case of high-level corruption, and has become a significant financial drain, with its annual budget rising to over ₹62 crore (about $7.4 million) without delivering any commensurate results. It has squandered its moral authority and lost public trust. Prominent senior advocates like Dushyant Dave have explicitly called for it to be disbanded.

Yet, there remains a compelling counter-argument. Activists like Nikhil Dey, a key figure in India’s transparency movement, insist that the institution is “absolutely needed” to address political corruption at the highest levels. The problem, they argue, lies not in the concept of an independent ombudsman but in its deliberate political emasculation. To abolish the Lokpal now, they contend, would be to concede victory to the very forces of corruption it was created to challenge. The solution is not abolition but radical reform: amending the law to remove structural flaws, ensuring a truly independent and transparent appointment process, and guaranteeing the full and immediate operationalization of its independent machinery.

A Dream Derailed

The journey of the Lokpal, from a beacon of hope forged in the fires of a mass movement to a moribund and mocked bureaucracy ordering luxury cars, is a cautionary tale of institutional decay. It was an institution born of public anger, legislated with immense power, but systematically hollowed out by political will and starved of the resources and independence it needed to succeed.

Its failure has broader implications for India’s democracy. It represents the weakening of yet another institution of accountability, a process that critics argue has accelerated in recent years. The Lokpal was meant to be the ultimate check on executive power, an institution that stood outside the traditional structures of government and answered only to the public. Its descent into irrelevance leaves a critical void in the country’s anti-corruption framework.

The debate over its future—whether to abolish a failed experiment or to fight for the soul of a vital idea—remains unresolved. But as the controversy rages, the image of seven gleaming white BMWs, purchased with public money by the people’s protector, stands as a costly and poignant monument to a dream derailed. It forces a difficult question upon the world’s largest democracy: What does it mean when your most powerful anti-corruption watchdog becomes a symbol of the very culture it was created to destroy?