On the evening of January 21, more than 500 professionals—police officers, bankers, lawyers, prosecutors, and compliance experts—logged in for a two-hour webinar that reflected a growing anxiety within India’s financial and law-enforcement systems, organised by Centre for Police Technology (An Algoritha Initiative). The subject was not abstract policy, but a very real operational dilemma: how, when, and under what authority bank accounts should be frozen or unfrozen in cyber-fraud cases.

The discussion centred on the newly issued Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) of the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) under the Ministry of Home Affairs—a document that has quickly become essential reading for anyone dealing with digital fraud, money laundering, or online financial abuse. At stake are thousands of accounts frozen each month, often without clarity for victims, banks, or even investigating officers.

Inside the I4C SOP: Law, Technology, and the 1930 Helpline

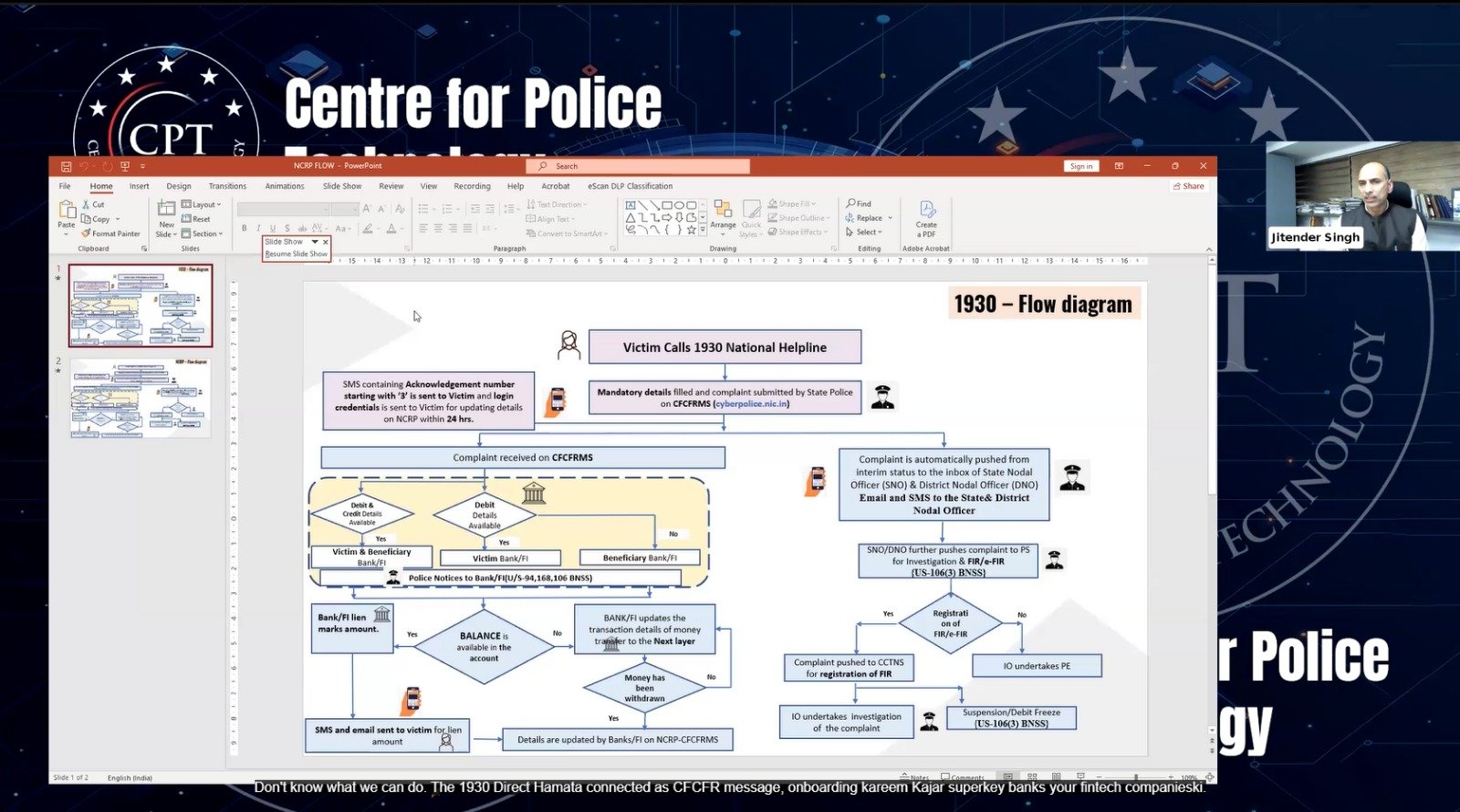

Opening the discussion was Mr. Jitendra Singh, Assistant Commissioner of Police at I4C, who walked participants through the operational architecture of India’s cyber-crime response—from the 1930 national helpline to the CFCFRMS/NCRP platforms that now serve as the backbone of complaint intake and inter-agency coordination.

Using flow diagrams and live case illustrations, Singh explained how complaints move from victims to banks, state nodal officers, and investigating units, and how account freezes are triggered even before an FIR is registered. The emphasis, he noted, is speed—because in cyber fraud, delays often mean permanent loss of funds.

Yet that very speed has produced friction. Victims whose accounts are frozen, or innocent account holders caught in laundering chains, often find themselves trapped in procedural limbo. The SOP, Singh argued, is an attempt to standardise responses while preserving legal safeguards under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita and allied laws.

Courts, Compensation, and the Problem of Over-Freezing

If Singh outlined the system’s design, Advocate (Dr.) Prashant Mali, a leading cyber-law expert, examined its legal stress points. Drawing on case law—including Supreme Court and High Court rulings—Mali highlighted how indiscriminate or prolonged freezing of accounts can violate constitutional protections and undermine trust in the system.

He underscored a recurring problem: technical jargon and incomplete understanding of financial workflows often lead to blanket freezes, even when partial debit restrictions or transaction-level monitoring would suffice. Judges and magistrates, he argued, are increasingly being asked to adjudicate complex digital disputes without adequate institutional training.

The SOP, Mali noted, is a corrective step—but only if it is accompanied by capacity-building for police, banks, prosecutors, and the judiciary. Otherwise, the risk is that a victim-centric tool becomes another source of legal contestation.

A Rare Conversation Across Silos

The webinar—also scheduled to feature Ankush Mishra, Deputy Superintendent of Police, Uttarakhand (who was unable to attend due to urgent official duties)—stood out for the breadth of its participation. Bank officials raised concerns about compliance risk; police officers spoke about pressure to act within minutes; lawyers questioned accountability when freezes persist for months.

What followed was an unusually candid exchange of questions and answers, reflecting a shared recognition: cybercrime response can no longer function in silos. Freezing a bank account is not merely an administrative act—it is an intervention with legal, economic, and human consequences.

By the end of the session, one theme was clear. As India’s digital economy expands, so too does the complexity of financial crime. The I4C SOP is not a final answer, but a living framework—one that will succeed only if institutions learn to speak a common language across law, technology, and justice.