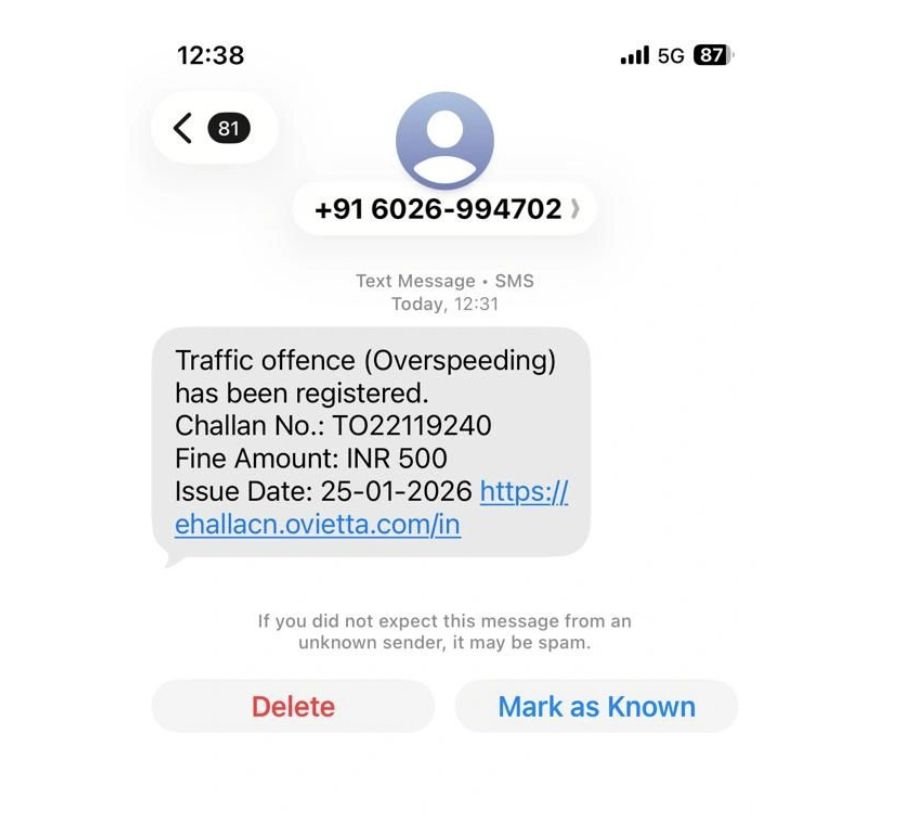

NEW DELHI: Millions of Indians received alarming SMS alerts claiming an unpaid traffic challan, often carrying a suspicious link and demanding immediate payment. The messages looked official. The sender was a regular 10-digit Indian mobile number. Many paid. Many more clicked.

What most recipients did not know was that these messages were not being sent from a central spam server or a foreign number, but from the phones of ordinary Indian citizens whose devices had been silently turned into tools of cybercrime.

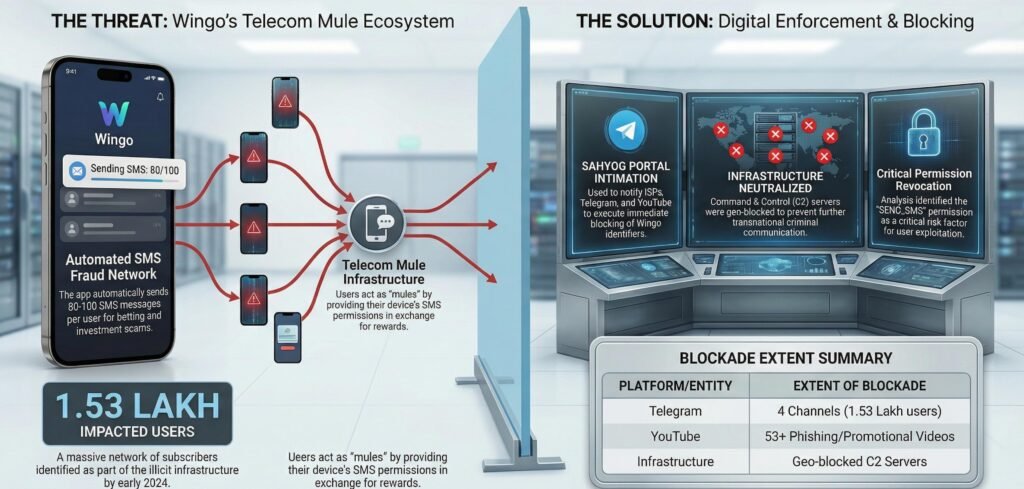

This week, that hidden infrastructure was exposed and disrupted after a coordinated crackdown by the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), targeting a transnational SMS bot network operating through an Android app called Wingo.

The Crackdown: Swift and Coordinated Action

Acting on multiple complaints from citizens across India, I4C launched what officials described as a “decisive strike” against the criminal infrastructure. The enforcement action, announced via the official @Cyberdost Twitter account, was comprehensive and immediate.

“Warning for Android users – Fraud SMS were being sent from users’ phones via the Wingo app without their knowledge” I4C announced, alerting the public that fraudulent SMS messages were being sent from users’ phones without their knowledge through the Wingo app.

🚨 Warning for Android users – Wingo app के ज़रिये users के phone से बिना उनकी जानकारी के fraud SMS भेजे जा रहे थे

I4C और MHA ने action लिया:

• Wingo के Command & Control servers geo-block किए गए

• 1.53 lakh users वाले 4 Telegram channels और 53+ YouTube videos block किए गए pic.twitter.com/pY5i6RGwuj

— CyberDost I4C (@Cyberdost) January 29, 2026

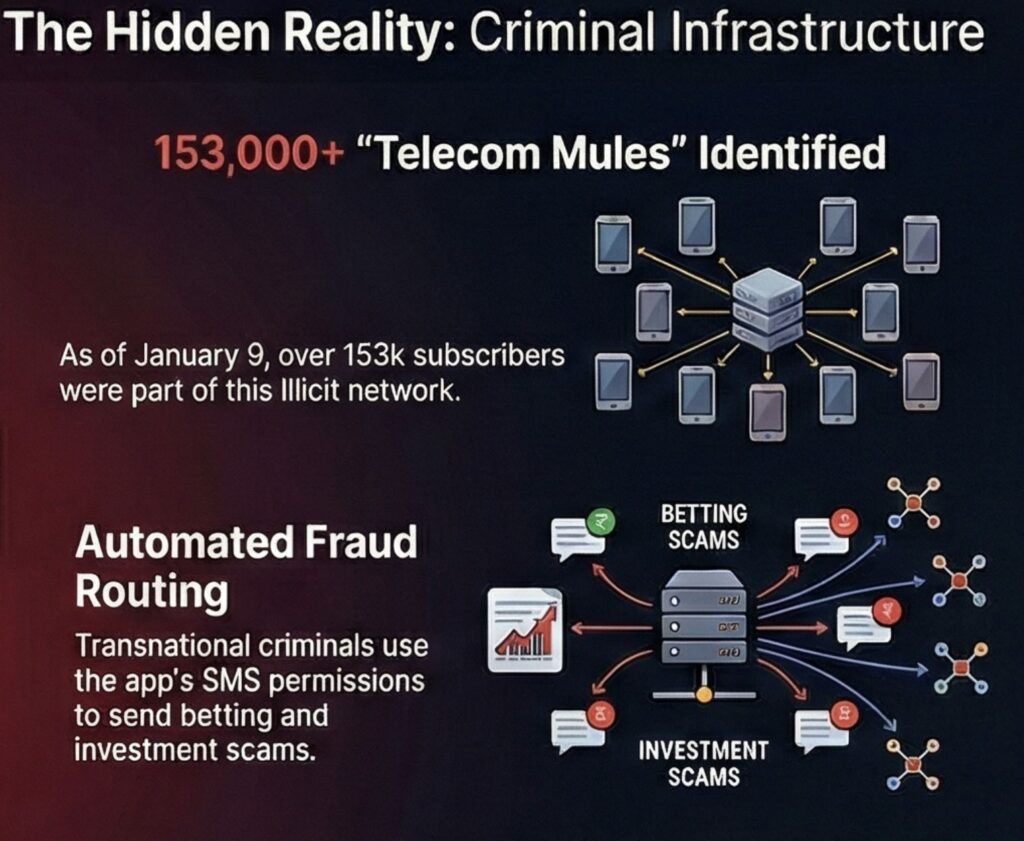

The scale of the operation was staggering. Over 1.53 lakh Android users had unknowingly become “telecom mules” — their devices hijacked to send between 80 to 100 fraudulent messages daily. That translates to an estimated 1.53 crore spam messages flooding Indian mobile networks every single day.

I4C’s response was surgical:

- Command and Control Servers Geo-Blocked: The digital command centers used by criminals to control infected devices were completely blocked within India, severing the operators’ ability to send new instructions.

- Four Telegram Channels Blocked: Channels with a combined subscriber base of 1.53 lakh users that were actively promoting and distributing the malicious app were shut down.

- 53+ YouTube Videos Removed: Promotional content showing fake testimonials and earning proofs was scrubbed from the platform.

- App Infrastructure Disabled: The entire misuse infrastructure across India was effectively disabled, preventing the daily deluge of 1.53 crore fraudulent messages from reaching potential victims.

“This action has immediately stopped the flood of fake e-challan messages that had been plaguing citizens for months,” confirmed a senior official involved in the operation who requested anonymity due to the ongoing nature of investigations.

The Scale of Deception: An Industrial Fraud Operation

The probe began when investigators noticed a pattern in e-challan-related credit and debit card fraud cases. The SMS alerts were coming from legitimate Indian mobile numbers — not international codes or obvious spam sources.

“This is criminal infrastructure on an industrial scale,” a senior officer explained. “By using genuine mobile numbers of ordinary citizens, scammers were able to bypass telecom filters and evade law enforcement detection. Every infected device became a node in a massive distributed fraud network.”

The fraudulent messages sent through the Wingo network covered a spectrum of scams, including fake traffic e-challan phishing websites, investment frauds promising unrealistic returns, predatory loan apps, and illegal betting platforms. Each message carefully crafted to create urgency, fear, or greed — the classic triggers of fraud.

Investigators found that Wingo was never available on the Google Play Store — a critical red flag that many users overlooked in their pursuit of promised easy earnings. The app was distributed exclusively through Telegram channels and YouTube promotional videos, platforms that offered less oversight and faster viral spread.

‘Telecom Mule as a Service’: How Wingo Weaponized Your Phone

At the core of this operation was an insidious concept that investigators are calling “Telecom Mule as a Service” — a criminal business model that turns everyday citizens into unwitting infrastructure for fraud.

A “telecom mule” is an individual whose device is unknowingly co-opted by criminals to send fraudulent messages. Unlike financial mules who knowingly transfer stolen money, telecom mules often have no idea their phones are being used for criminal purposes. This allows criminals to hide their tracks and leverage lakhs of legitimate phone numbers for their scams, making them incredibly difficult to trace and block.

The Technical Mechanism:

Wingo accomplished this digital hijacking through two critical Android permissions requested during installation:

- SEND SMS Permission: This granted the app the ability to send text messages from the user’s device without their direct interaction or knowledge. Once granted, the app could fire off dozens of messages while the phone owner slept, worked, or went about their daily life, completely unaware.

- REQUEST INSTALL PACKAGES Permission: This allowed the app to install other malicious applications without user consent, opening the door for further compromise. Once inside, Wingo could potentially install additional malware, keyloggers, or data harvesting tools, turning a single bad decision into a cascading security nightmare.

The Business Model:

In a particularly cynical twist, Wingo created a self-sustaining financial ecosystem. Criminals running illegal gambling operations would route their deposit proceeds to these telecom mules as payment for completing “SMS Tasks.” Users thought they were earning money through legitimate micro-tasks. In reality, they were being paid with proceeds from other victims’ losses to facilitate fraud against even more victims.

It was a perfect closed loop: gambling fraud funded the SMS infrastructure, which recruited more victims for gambling fraud, which funded more SMS sending, which recruited more victims. Each participant became both victim and unwitting accomplice.

The Bait: How Victims Were Recruited and Trapped

The Wingo operation followed a sophisticated psychological manipulation playbook:

Phase 1 — The Lure: Aggressive marketing across Telegram channels and YouTube positioned Wingo as “THE TOP ONLINE MONEY EARNING APP WITHOUT INVESTMENT IN INDIA.” Promotional material featured smiling people holding cash, promises of “easy tasks to get bonus,” “super-fast withdrawal,” and referral earnings. The pitch was simple: download, complete tasks, earn money — no investment required.

Phase 2 — Building Trust: New users received small payments quickly. ₹50 here, ₹100 there. Withdrawals processed instantly. This wasn’t generosity — it was investment. These small payouts created credibility and encouraged users to continue, recruit friends, and grant additional permissions.

Phase 3 — The Hook: Once engaged, users were told they needed to deposit money to “unlock” higher-earning tasks or maintain their account status. Payments were routed through UPI or personal wallets — never through secure banking channels — making transactions difficult to trace and impossible to reverse.

Phase 4 — Data Harvesting: The app requested access to contacts, photo gallery, and precise location. Users, already invested and trusting, often granted these permissions without hesitation. This gave criminals a treasure trove of personal data that could be monetized separately or used for targeted attacks.

Phase 5 — The Payload: Users were assigned “SMS Tasks” or “Message Tasks” presented as legitimate promotional work. In reality, their phones began sending 80 to 100 messages daily promoting e-challan phishing sites, investment scams, and predatory loan apps. Most users had no idea what messages were being sent or to whom.

Phase 6 — The Pyramid: To exponentially expand the network, Wingo employed a referral-based structure. Users were encouraged to recruit friends and family, earning bonuses for each new “team member.” This created a pyramid scheme dynamic where victims became recruiters, spreading the malware through trusted social networks.

Phase 7 — The Exit: After extracting maximum value — through deposited funds, harvested data, and sent messages — accounts were blocked. Fake customer care numbers led nowhere. Support channels vanished. In many cases, as complaints mounted, the app would disappear from distribution channels entirely, only to resurface under a new name with the same underlying infrastructure.

“The sophistication is remarkable,” noted a cybersecurity analyst familiar with the case. “Every step is designed to overcome natural skepticism, exploit cognitive biases, and keep users engaged until they’re too deep to back out easily.”

The Chinese Connection: Digital Fingerprints Point to Xiamen

The evidence linking Wingo to Chinese operators is technical and verifiable. Cybersecurity researchers analyzing the application’s code discovered that it is signed with the default development certificate for the Cocos2d-x game engine — a legitimate game development framework. However, the certificate contains embedded location details: Xiamen, Fujian, China.

This forensic evidence aligns with broader patterns observed by Indian law enforcement. Chinese involvement in digital fraud networks targeting Indian citizens has become increasingly common, ranging from loan app scams to cryptocurrency frauds. The Wingo operation represents an evolution — moving from simple phishing to building complex, distributed criminal infrastructure.

“If you are investigating e-challan-related credit or debit card fraud, and the message has come from a 10-digit Indian mobile number, there’s a high chance that this message was sent via telecom mule APKs like Wingo or similar variants such as Rupee Rush,” investigators told The420.in.

The transnational nature of the operation complicates law enforcement efforts. While I4C can block infrastructure within India and remove promotional content from platforms, pursuing the actual operators requires international cooperation and jurisdictional navigation that can take months or years.

Unwitting Accomplices: The Legal Jeopardy Facing Victims

One of the most troubling aspects of the Wingo case is the potential legal exposure facing victims who believed they were simply earning extra income.

“In several cases, users who initially receive small benefits unknowingly become links in scam chains, exposing themselves to possible legal consequences,” warned a senior investigating officer. “Their phone numbers appear in victim complaints. Their devices sent the fraudulent messages. Proving they were unwitting rather than willing participants can be challenging.”

The officer emphasized that most users have no idea they’re facilitating organized crime: “The sophistication of these schemes means people don’t realize they’re becoming part of a criminal enterprise. They think they’re doing legitimate micro-tasks, not facilitating fraud against other citizens.”

Authorities have indicated that genuine victims who installed Wingo unknowingly and immediately remove it upon learning its true purpose will not face prosecution. However, the legal landscape remains murky for those who continued using the app after receiving warnings or those who actively recruited others knowing or suspecting the app’s fraudulent nature.

Protecting Yourself: Essential Guidance for Android Users

In the wake of the Wingo exposure, I4C has issued comprehensive guidance for protecting against similar threats:

Critical Red Flags:

- Any app claiming guaranteed or fixed daily profits

- Applications unavailable on official app stores (Google Play Store, Apple App Store)

- Apps requesting SMS permissions when such functionality is unrelated to their stated purpose

- Schemes requiring upfront payment to “unlock” earnings or “maintain account status”

- Aggressive referral-based earning structures resembling pyramid schemes

- Payment exclusively through UPI IDs, personal wallets, or cryptocurrency — never institutional banking

Essential Protective Measures:

- Verify app legitimacy through official sources before downloading anything

- Scrutinize permission requests carefully — why does a “task app” need SMS access?

- Never pay money upfront to earn rewards or complete tasks

- Avoid making payments to unknown UPI IDs or scanning unfamiliar QR codes

- Never share OTPs, bank details, or card information regardless of the stated reason

- Immediately uninstall suspicious apps and report them through official channels

- Review your phone’s SMS logs periodically for unfamiliar sent messages

If You’ve Been Affected:

Victims should take immediate action:

- Call 1930: Contact the National Cybercrime Helpline immediately

- File Official Complaint: Report the incident on cybercrime.gov.in with detailed information

- Block Transactions: Contact your bank or UPI provider to block suspicious transactions immediately

- Uninstall Immediately: Remove the malicious app and any other apps it may have installed

- Factory Reset (if possible): For maximum security, consider backing up legitimate data and performing a factory reset

Time is critical. Swift action can prevent further financial losses, protect your data, and help law enforcement track the perpetrators.

A New Era of Distributed Cybercrime

The Wingo case represents a significant evolution in cybercrime methodology. Rather than simply stealing credentials or money directly, modern fraud operations are building complex, distributed infrastructure that turns victims into unwitting accomplices.

“This is ‘Crime as a Service’ at its most insidious,” explained a cybersecurity researcher familiar with the investigation. “By distributing the criminal activity across hundreds of thousands of legitimate devices, operators achieve massive scale while maintaining anonymity. Traditional blocking methods become ineffective when every message comes from a real person’s phone number with a legitimate telecom connection.”

The implications extend beyond immediate financial fraud. Each compromised device becomes a data collection point, potentially harvesting contacts, photos, locations, and behavioral patterns. This data can be weaponized for targeted attacks, sold on dark web markets, or used for identity theft.

Moreover, the psychological damage to victims who discover they’ve been facilitating fraud is profound. “There’s shame, guilt, fear of legal consequences,” noted a victim support counselor. “People feel violated and complicit simultaneously. They were trying to earn honest supplementary income and ended up as tools in a criminal operation.”

Looking Forward: The Long Fight Ahead

While I4C’s dismantling of the Wingo network represents a significant victory, officials acknowledge this is one battle in a much larger war.

“We need a multi-pronged approach,” the offcier emphasized. “Enforcement action alone isn’t enough. We need sustained public awareness campaigns, better platform governance to prevent app distribution outside official stores, enhanced permission frameworks in mobile operating systems that make dangerous permissions harder to grant accidentally, and robust international cooperation to pursue operators in other jurisdictions.”

The case has prompted calls for regulatory reform, including mandatory security audits for financial applications, stricter penalties for apps that misuse granted permissions, and enhanced cooperation between Indian authorities and international law enforcement agencies, particularly in China.

Investigators have identified similar suspicious applications including “Rupee Rush” and are investigating whether these represent variations of the same criminal infrastructure or separate but related operations. The pattern suggests a franchise model, where successful fraud methodologies are replicated under different brand names to evade detection.

For now, the immediate threat from Wingo has been neutralized. Its Command and Control servers remain blocked, distribution channels have been shut down, and the promotional ecosystem has been dismantled. But criminals adapt quickly. New apps will emerge, using similar techniques under different names.

The fundamental message from investigators remains clear: Legitimate income sources do not require users to send indiscriminate messages, do not demand excessive device permissions unrelated to functionality, and do not operate in the shadows outside regulatory approval.

If an opportunity seems too good to be true, demands trust without transparency, or requires you to compromise your device security, it almost certainly is a scam. In the digital age, vigilance is not optional — it’s essential for survival.

WINGO OPERATION: KEY FACTS AT A GLANCE

| Category | Details |

| Affected Users | 1.53 lakh+ Android users identified as telecom mules |

| Daily Message Volume | 80-100 fraudulent SMS per infected device; ~1.53 crore total daily |

| Fraud Types Distributed | Fake traffic e-challans, investment scams, predatory loan apps, illegal betting platforms |

| Suspected Origin | Xiamen, Fujian, China (verified via Cocos2d-x development certificate) |

| Critical Permissions Exploited | SEND_SMS (silent message sending), REQUEST_INSTALL_PACKAGES (malware installation) |

| Distribution Channels | Telegram channels, YouTube promotions (NOT on Google Play Store) |

| Enforcement Actions | C2 servers geo-blocked; 4 Telegram channels (1.53L users) blocked; 53+ YouTube videos removed; infrastructure disabled |

| Lead Investigator | DCP (Cyber) Shavya Goyal, Gautam Budh Nagar Police Commissionerate |

| Victim Reporting | National Cybercrime Helpline: 1930 | Portal: cybercrime.gov.in |