NEW DELHI: As India’s digital footprint expands to over one billion users, a parallel economy of “cybercrime-as-a-service” has emerged. At a high-level summit in New Delhi, officials detailed a landscape where a victim is claimed every 37 seconds, prompting a massive state effort to secure the world’s most active digital transaction corridor.

The Industrialization of the Breach

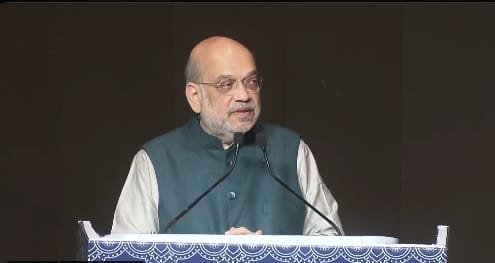

In a conference room in New Delhi, the scale of India’s digital vulnerability was laid bare not as a series of isolated glitches, but as an industrialized sector of the shadow economy. Union Home Minister Amit Shah, addressing a delegation at the “Tackling Cyber-Enabled Frauds & Dismantling the Ecosystem” conference, described an evolution in criminal methodology. Cybercrime has moved beyond the “lone wolf” attacks of the past decade into organized, systematic operations where bank accounts are bought and sold with the efficiency of a legitimate service industry.

The data suggests a relentless pace. According to current estimates, one person in India falls victim to cybercrime every 37 seconds—a rate that translates to roughly 100 people every hour. For the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C), the challenge is no longer just manual hacking but combating automated, complex techniques that exploit the country’s rapid digital integration.

Certified Cyber Crime Investigator Course Launched by Centre for Police Technology

A Billion Nodes of Vulnerability

The crisis is, in many ways, a byproduct of India’s success in the digital domain. Eleven years ago, the country counted 250 million internet users; today, that number has surpassed one billion. This massive migration online has turned India into a global leader in digital payments, with officials noting that every second digital transaction in the world now occurs within the country.

However, this high volume of transactions has created a vast surface area for fraud. The transition from a cash-heavy society to a digital-first economy has occurred with such velocity that the security infrastructure is in a constant state of catch-up. Shah underscored that securing these transactions has shifted from a matter of consumer protection to a “national security threat,” necessitating a move beyond traditional policing methods to stay ahead of criminals who adopt new technologies as quickly as the banks they target.

The Ledger of Loss and Recovery

Between January 2020 and late 2025, the I4C reporting portal became a primary barometer for the nation’s digital anxieties, accessed more than 230 million times. The raw numbers provided by the Home Ministry paint a picture of a strained but active defensive line. Out of 8.2 million registered complaints, 184,000 have been converted into First Information Reports (FIRs), the formal opening of a police investigation.

The financial stakes are significant. Total fraud during this period is estimated at approximately Rs 20,000 crore. Through the coordination of 62 banks and financial institutions, authorities have managed to freeze or return Rs 8,189 crore to victims. The crackdown has also extended to the physical tools of the trade: by December 2025, the Ministry had cancelled over 1.2 million suspicious SIM cards and blocked the IMEI numbers of more than 300,000 mobile devices. To date, 20,853 individuals have been arrested in connection with these cases.

The Credibility of the 1930 Line

As the volume of complaints rises—from 52,000 in 2021 to 86,000 in the most recent reporting period—the government’s focus has narrowed on the “1930” national helpline. The efficacy of this single point of contact is now viewed as the linchpin of the state’s response. Officials have called for a surge in call handlers across all police units, citing the narrow window of time available to intercept stolen funds.

The urgency is driven by a simple, mathematical reality: if a victim’s call goes unanswered during the initial minutes of a breach, the money is often moved through multiple layers of “bought” accounts, making recovery nearly impossible. The reliability of this response time is being treated as a test of the state’s credibility in the digital age. As the ecosystem of fraud grows more sophisticated, the mandate for the I4C and its banking partners is to reduce response times to a point that matches the speed of the transactions themselves.