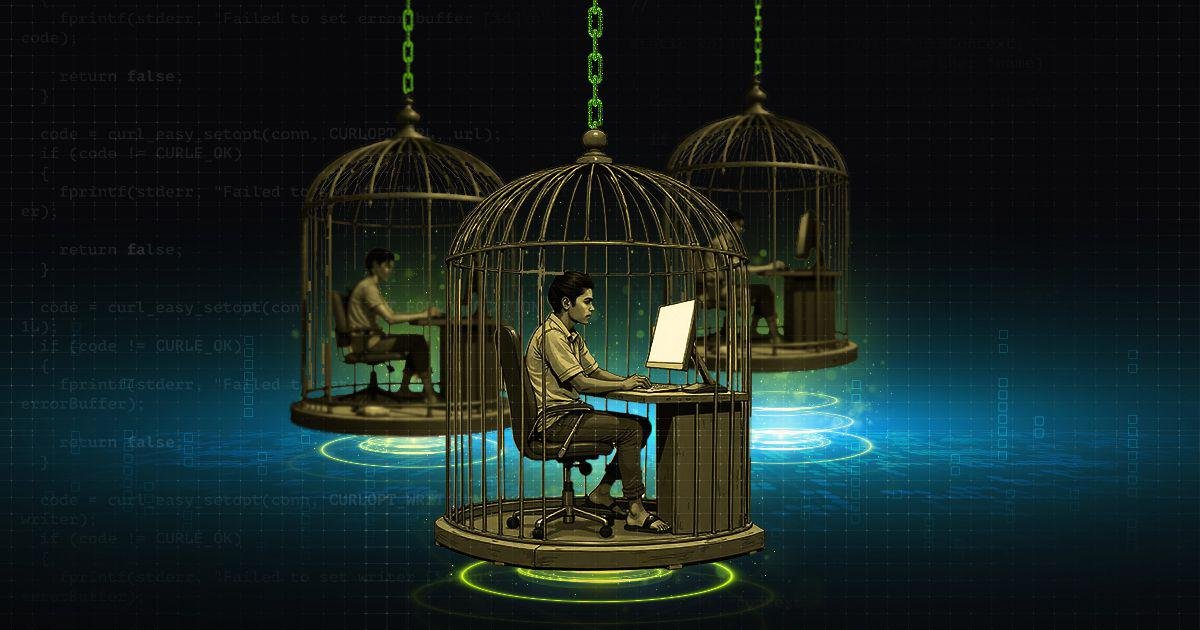

Ahmedabad / New Delhi: What began as a dream for a stable income and a respectable job abroad turned into a nightmare for scores of young men from Gujarat. Promised legitimate data-entry and call-centre work in Thailand, they were instead trafficked into cybercrime compounds in Myanmar forced to work as modern-day digital slaves. These operations, police say, are part of a sprawling international network with deep links to Chinese handlers and criminal syndicates across Southeast Asia.

Twenty-three-year-old Jignesh (name changed) from Ahmedabad left for Bangkok in December 2024, full of hope. Through a social media ad, he had found a recruiter offering a data-entry job for 25,000 Thai Baht (around ₹70,000 per month), with free accommodation and visa assistance. But the moment he landed in Bangkok, the promises began to crumble.

He was taken to a hotel outside the city, made to wait for hours, and later driven overnight toward the Thai–Myanmar border. Under the cover of darkness, the group was ferried across the Moei River into Myanmar into a walled compound guarded by armed men.

“They told us we were no longer employees, but debtors,” Jignesh recalls. “If we wanted to return, we had to pay between three and four lakh rupees.”

His father, a security guard earning ₹15,000 a month, mortgaged their small home to raise ₹3.75 lakh. Only after weeks of pleading and payments was Jignesh allowed to leave. He returned to Ahmedabad thinner, traumatized, and deeply indebted.

‘They Didn’t Give Us Work They Trained Us to Scam’

Survivors describe gruelling schedules inside these camps — 15 to 18 hours of forced work every day after a two-week “training period.” There, they were taught how to defraud people online.

Some were trained to run “romance scams,” posing as women online to deceive men in the U.S. and Europe into investing in fake ventures. Others were assigned to India-focused fraud units calling people while posing as police officers, TRAI or RBI officials, and coercing victims under the pretext of “digital arrest” or Aadhaar misuse.

“If you didn’t meet the daily fraud target, they withheld food or beat you,” says Tanmay (name changed), another victim from Ahmedabad.

The Gujarat Connection and the Mastermind

Once repatriated, the victims’ statements led the Gujarat Cyber Crime Cell to a startling name “Neel,” later identified as Nilesh Purohit (39). Investigators say Purohit interviewed youths from Ahmedabad and Surat, arranged their travel and visas, and handed them over to fraudulent companies operating from Thailand and Myanmar. He worked under a Chinese handler known as “Yamaha.”

On November 16, police intercepted Purohit at Ahmedabad airport while he was allegedly trying to flee to Malaysia. The probe revealed he had trafficked more than 500 Indians to cybercrime hubs in Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia.

Gujarat Deputy Chief Minister Harsh Sanghvi said Purohit ran a global recruitment syndicate with over 126 sub-agents operating across South Asia, including Pakistan. He reportedly earned between $2,000 and $4,500 per recruit, sharing up to 40% commission with his agents. The funds moved through cryptocurrency wallets and mule bank accounts.

‘Project India’ — A New Operation

Police recovered two mobile phones and a laptop from Purohit, uncovering a chilling plan dubbed “Project India.” The project aimed to recruit 1,000 new Indian youths into cyber-slavery hubs across Southeast Asia, with $4,000 commissions per recruit.

IPS officer Rajdeepsinh Zala said the seized data contained photos of over 2,000 Indians and even a video showing the torture of a foreign woman.

“He monitored Interpol’s wanted list to check if his name appeared before planning his next move,” Zala revealed.

Investigations also found that many of these cybercrime networks now use AI-generated images and videos to deceive victims online. Fake profiles, AI-powered video calls, and even hired models were used to lend authenticity to the scams.

‘They Returned, but the Fear Remains’

Another survivor, Dhaval Joshi (name changed), described Myanmar’s K.K. Park as a fortress-like complex filled with hundreds of foreign captives.

“We believed it was a legal call centre,” he said. “Only later we realized we were cyber slaves.” Joshi was also offered ₹2–3 lakh to lure more Indians into the trap but refused.

Today, many of these young men are back in Gujarat, trying to rebuild their lives under heavy debts. The families that once dreamed of prosperity are now struggling to repay the loans that bought their sons’ freedom.

Police officials admit to a new worry that some of these victims, having learned sophisticated fraud techniques, could be tempted into cybercrime themselves. The Gujarat Cyber Crime Cell has placed several returnees under quiet observation to ensure the cycle of cyber slavery does not take root within India again.