The Supreme Court’s recent ruling mandating a minimum of three years of practice at the Bar before a candidate can appear for the Civil Judge (Junior Division) examination is aimed at enhancing judicial competence. By insisting that future judges gain practical exposure to court procedures and litigant realities, the decision seeks to raise the quality of the judicial system. However, this seemingly progressive reform carries significant unintended consequences for thousands of fresh law graduates especially women and first-generation lawyers.

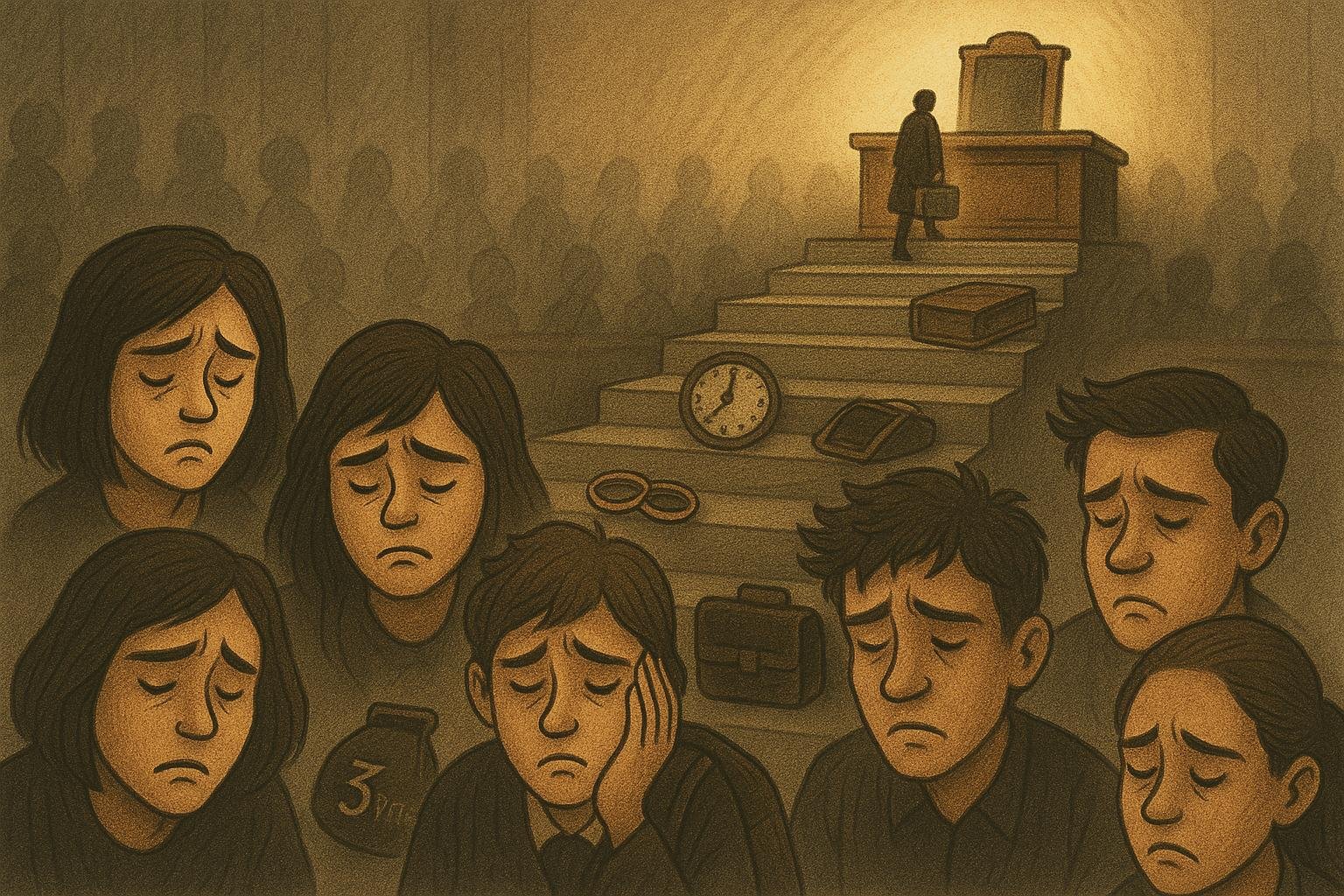

For many aspirants, judicial services aren’t just another career option they represent a rare opportunity for stability, dignity, and meaningful public service. The exam has long been a leveller in a legal field. The new three-year practice requirement, though framed in the interest of judicial maturity, risks deepening this divide by placing an additional burden on those who already have limited access to resources and networks.

Women bear the brunt of this shift. In a society where timelines for marriage and family are often rigid, delaying career entry by three years can lead to young women being pushed away from legal careers entirely. Without institutional support, mentorship, or safe workspaces in litigation still largely male-dominated many may opt out before they ever begin.

Furthermore, the assumption that these three years will offer productive, formative legal experience is not realistic for most. Law firms often prefer elite graduates, and junior lawyers frequently work for stipends as low as ₹15,000–₹20,000, without structured guidance. First-generation lawyers face the additional challenge of breaking into closed professional circles with little support.

The Court’s intent is valid, but the reform must be holistic. For the judiciary to truly evolve, it must be built on inclusion, not just experience. Reform must not come at the cost of ambition.

Views expressed by author are personal.