NEW DELHI: In the labyrinthine corridors of India’s power structures, a quiet but pervasive system operates just beneath the surface. They are called “sahayaks”—a Hindi term meaning “assistants” or “helpers”—and their role extends far beyond the mundane tasks of fetching tea or filing papers. For ministers, civil servants, and judges, these shadowy figures have evolved into something more: proxies, negotiators, and, when necessary, fall guys in a high-stakes game of influence and evasion.

The phenomenon came into sharp focus recently when a prominent dermatologist-turned-social-commentator, known online as “The Skin Doctor,” took to X (formerly Twitter) to expose what he described as a systemic reliance on these intermediaries.

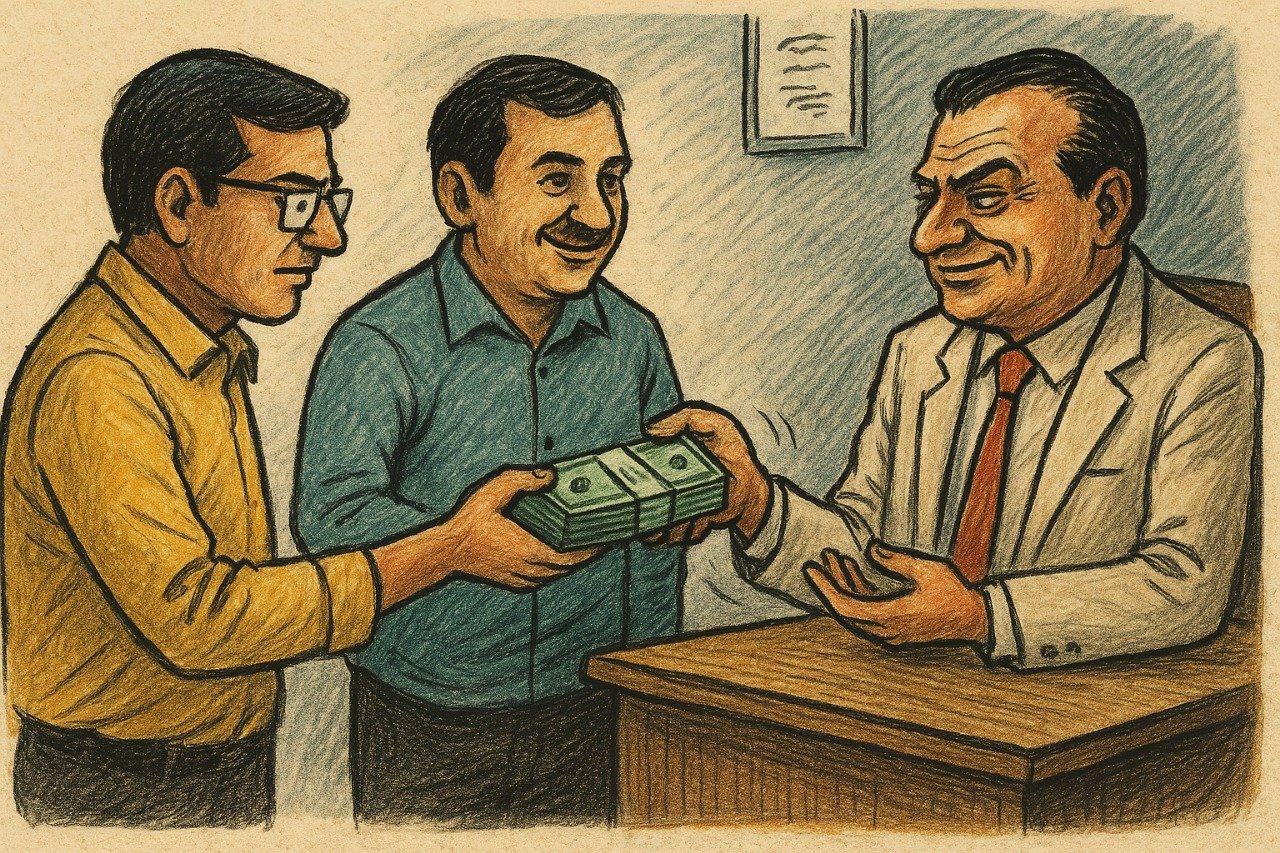

“Every politician, high-ranked govt official, judge, etc., has a ‘Sahyogi,’” he wrote on March 23, 2025. “Once a peon or driver doubling up, but now hired separately for extra security. This ‘Sahyogi’ negotiates and collects bribes on their behalf. Once the deal is done, they inform the official, who then acts.”

The post struck a nerve, garnering thousands of likes and retweets—proof that India is not just aware of the corruption within its systems, but also increasingly unafraid to confront it publicly.

The Sahayak as Scapegoat: Legal Loopholes and Layered Deniability

Historically, the term “sahayak” dates back to colonial times, when British officers used local aides for both personal and professional tasks. In today’s India, the military still uses sahayaks—though the practice faces criticism for being outdated. Outside the army, however, the sahayak has transformed into something far more controversial.

Empanelment for Speakers, Trainers, and Cyber Security Experts Opens at Future Crime Research Foundation

In the ministries of Delhi, state secretariats, and judicial corridors, sahayaks are no longer just errand-boys. They are chosen confidants—sometimes drivers, peons, or distant relatives—trusted not only for their loyalty but for their ability to act as shields from accountability.

“If a bribe is traced, it stops with the sahayak. The official can claim ignorance,” said a retired IAS officer who spoke on condition of anonymity. “It’s deniability built into the hierarchy.”

“The sahayak is the designated scapegoat,” said a white-collar crime lawyer in Delhi. “They’re poorly paid and expendable. The system exploits their loyalty—or their desperation.”

Judges, Ministers, and the Machinery of Influence

Even India’s judiciary has not remained untouched.

“A sahayak in court may not just collect money—they might whisper in the judge’s ear about which case to prioritize or delay,” said a legal scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “It’s influence peddling with insulation.”

For ministers, sahayaks often function as political fixers. A former aide to a cabinet minister recounted his role collecting “donations” in hotel lobbies and delivering coded updates.

“I’d say, ‘The file is ready’—that meant the money was in hand, and the policy could move forward.”

The sahayak system endures because it thrives on plausible deniability.

“It’s not about individuals—it’s structural. The lack of top-level accountability ensures the bottom rung always pays.”

For the sahayaks, the job is a double-edged sword. Some become rich; others become scapegoats. All operate in a legal and moral gray area.

The Skin Doctor’s viral post has reignited the demand for institutional reform—stricter vetting of public officials’ personal aides, more transparency in appointments, and accountability at the highest levels. But in a country where power is often wielded through intermediaries, dismantling the sahayak system may prove harder than exposing it.

For now, these invisible aides remain the hidden hands in India’s corridors of power—indispensable, expendable, and always in the shadows.